This blog post details our approach to the AI for Earthquake Response Challenge, organized by the ESA Φ-lab and the International Charter "Space and Major Disasters".

We secured 2nd place among over 250 teams by developing AI models capable of accurately detecting building damage from satellite imagery.

Challenge Overview

When an earthquake strikes, every minute counts. Rapid damage assessments can guide emergency responders to

the hardest-hit areas, prioritize resources, and ultimately save lives. But even with access to

satellite imagery, the task of mapping damaged buildings is still largely manual, and that takes time.

This is the problem that the AI for Earthquake Response Challenge, organized by the ESA Φ-lab and

the International Charter “Space and Major Disasters” set out to address.

The mission: build AI models capable of automatically detecting building damage from

satellite imagery accurately and at scale.

Post-event Pleiades image over Latakia, Syria with building polygons overlaid

(categorized by damage field, green = undamaged, grey = damaged) © CNES 2023, distribution Airbus DS.

The competition was structured in two phases to reflect both research

and real-world emergency response conditions:

-

Phase 1 (8 weeks) – We received pre- and post-event satellite images for 12 earthquake-affected sites.

Each site came with building footprint polygons, and most also included building-level damage labels.

The task was framed as a binary classification problem, where each building was labeled as either

0 (undamaged) or 1 (damaged). However, the setup varied:

- 7 sites were fully annotated and used for training.

- 4 sites - Adiyaman (Turkey), Antakya East (Turkey), Marash (Turkey), and Cogo (China) - were partially annotated, with some buildings labeled and others left unlabeled. The labeled portion could be used for training, while the unlabeled buildings were evaluated through the live leaderboard, where our predictions were scored against hidden ground truth. The scoring on the leaderboard was based on the F-score metric, which balances precision and recall. For this phase, we could submit predictions every 12 hours to the live leaderboard to see how our models performed.

- 1 site only included post-event imagery.

-

Phase 2 (10 days) – This was the real stress test. We were given pre- and post-event imagery for

2 completely new earthquake sites. Unlike Phase 1, no labels were provided—only the building polygons.

We had to generate predictions directly, without retraining on the new data. Again, the scoring was done via a live leaderboard using the F-score metric.

This phase tested whether our models could generalize and remain accurate. For this phase, we could submit predictions every 24 hours to the live leaderboard to avoid overfitting.

More than 250 teams participated, ranging from academic researchers to industry professionals.

Our Approach

To tackle the challenge, we iterated step by step, starting simple and gradually incorporating more complexity as we understood the dataset better.

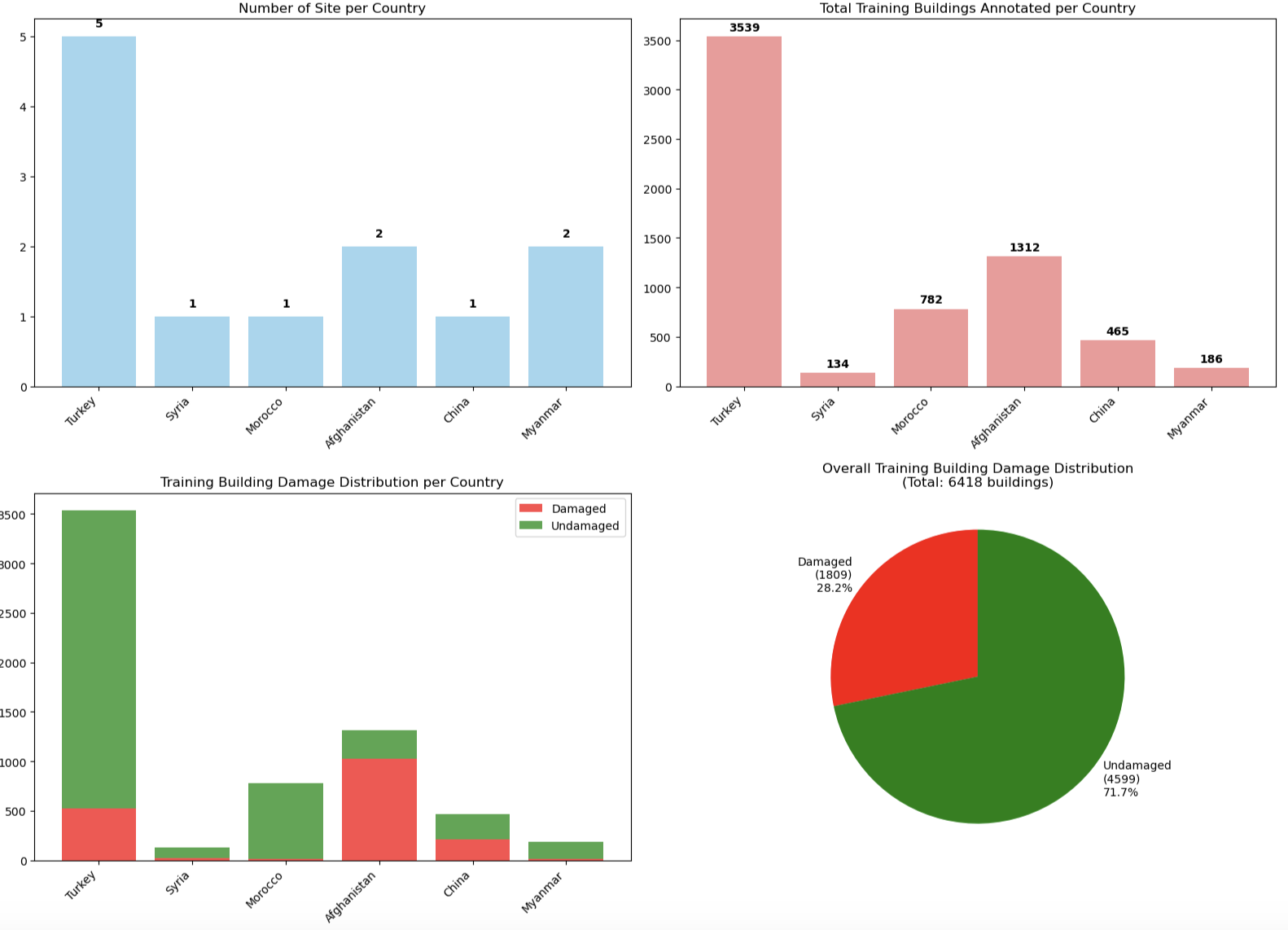

Data Exploration

The first step was to explore the dataset in detail. We:

- Plotted the building annotations on the satellite imagery to visually confirm alignment.

- Worked with GeoPandas and Rasterio to handle building polygons and raster data.

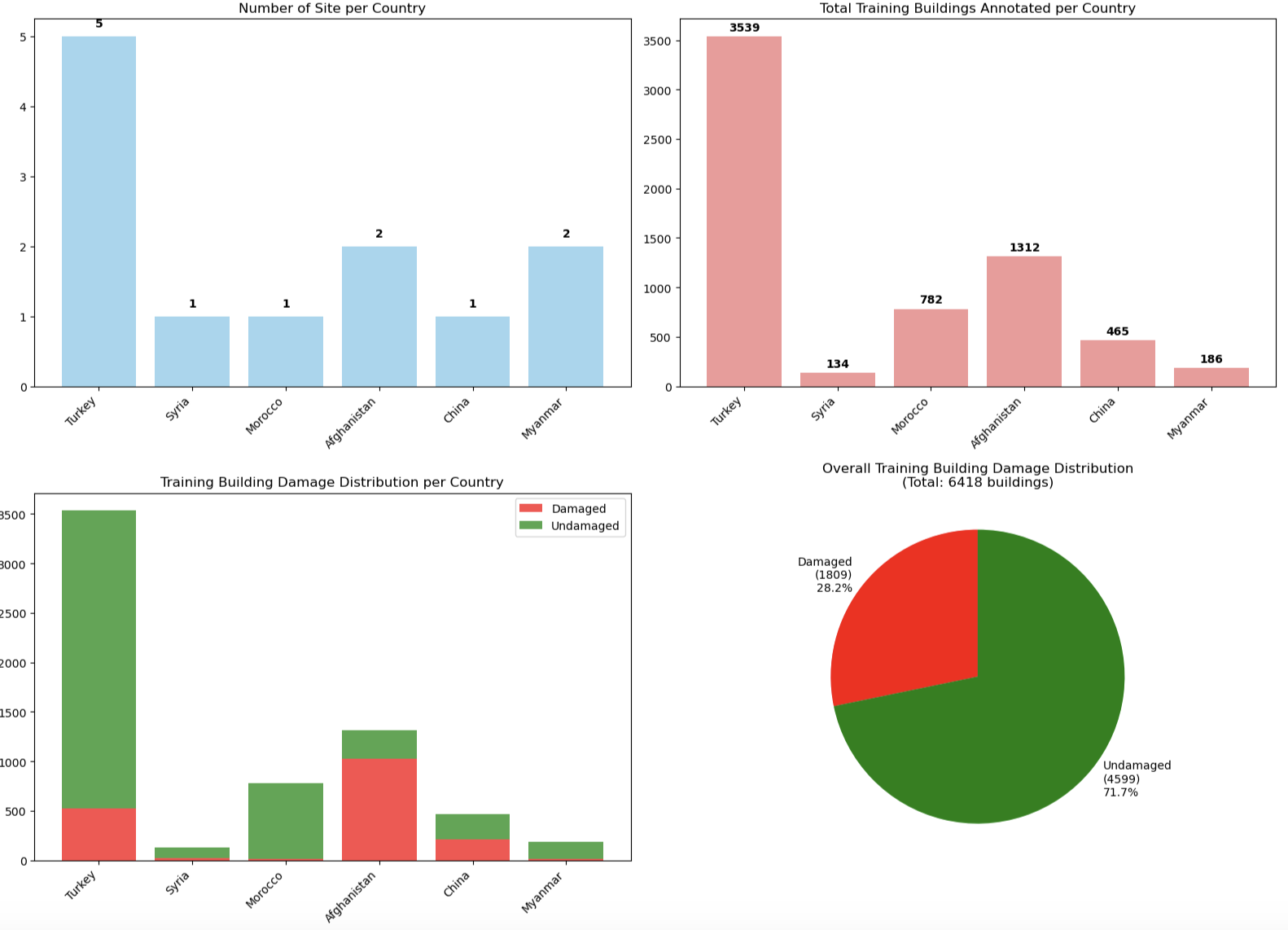

- Discovered that the dataset was imbalanced, with far more undamaged buildings than damaged ones.

Data exploration showing class imbalance (more undamaged buildings than damaged ones).

- Realized that if we wanted to use both pre- and post-event images effectively, we needed to perform image registration. Building annotations were provided only for the post-event imagery, and the pre-event images sometimes came from different satellites with slightly different angles, resolutions, or positions. Image registration adjusts one image so that it spatially aligns with another, ensuring that each building polygon matches the correct location in both images. More details on our registration approach are provided in the next section.

This early exploration shaped our modeling strategy.

First Model: Post-Event Only

As a baseline, we trained a model using only the post-event imagery. To do so, we extracted patches around building footprints.

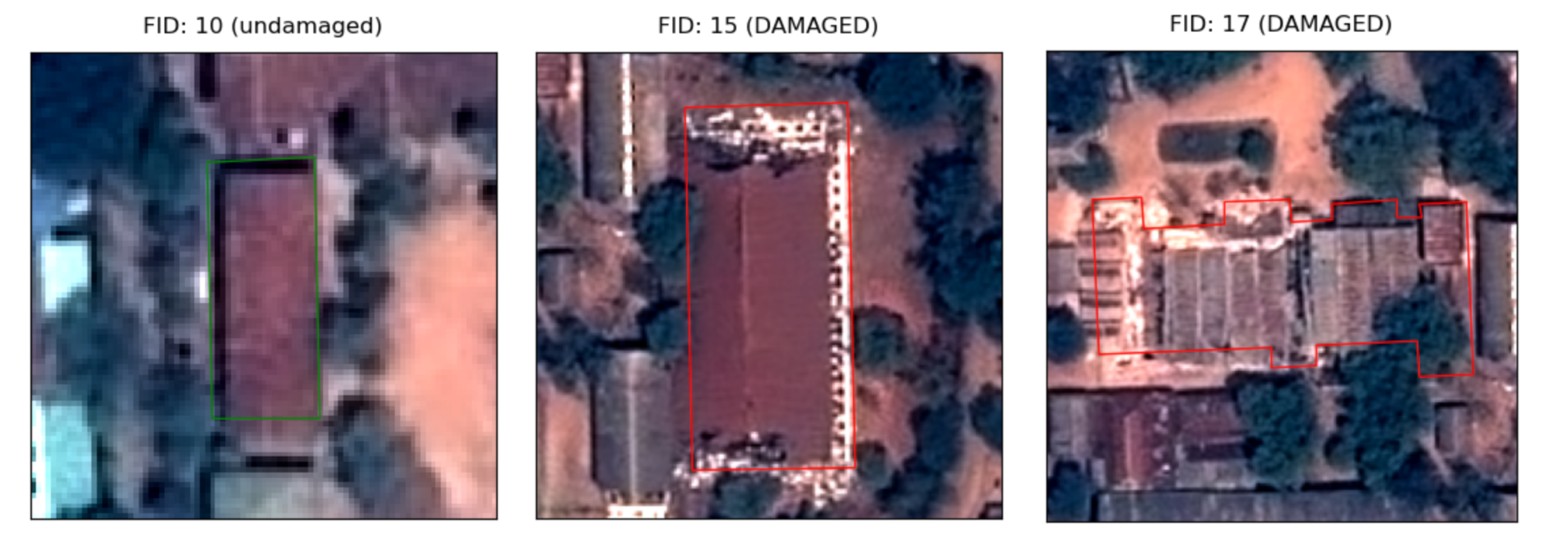

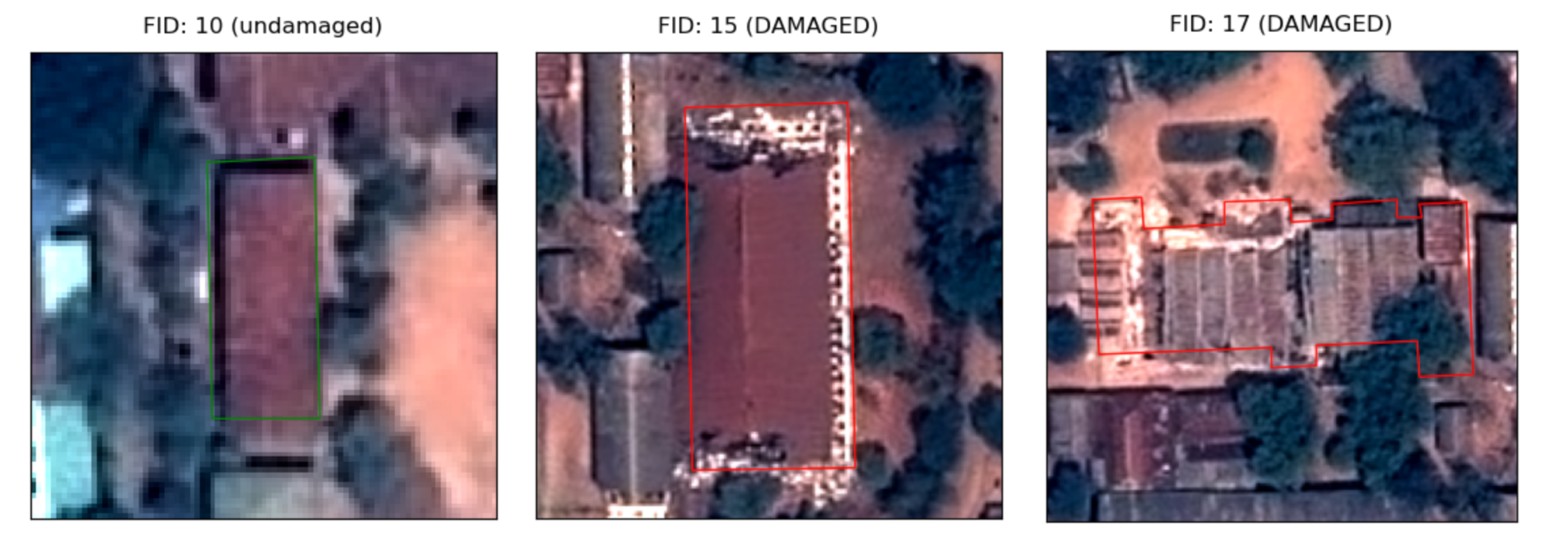

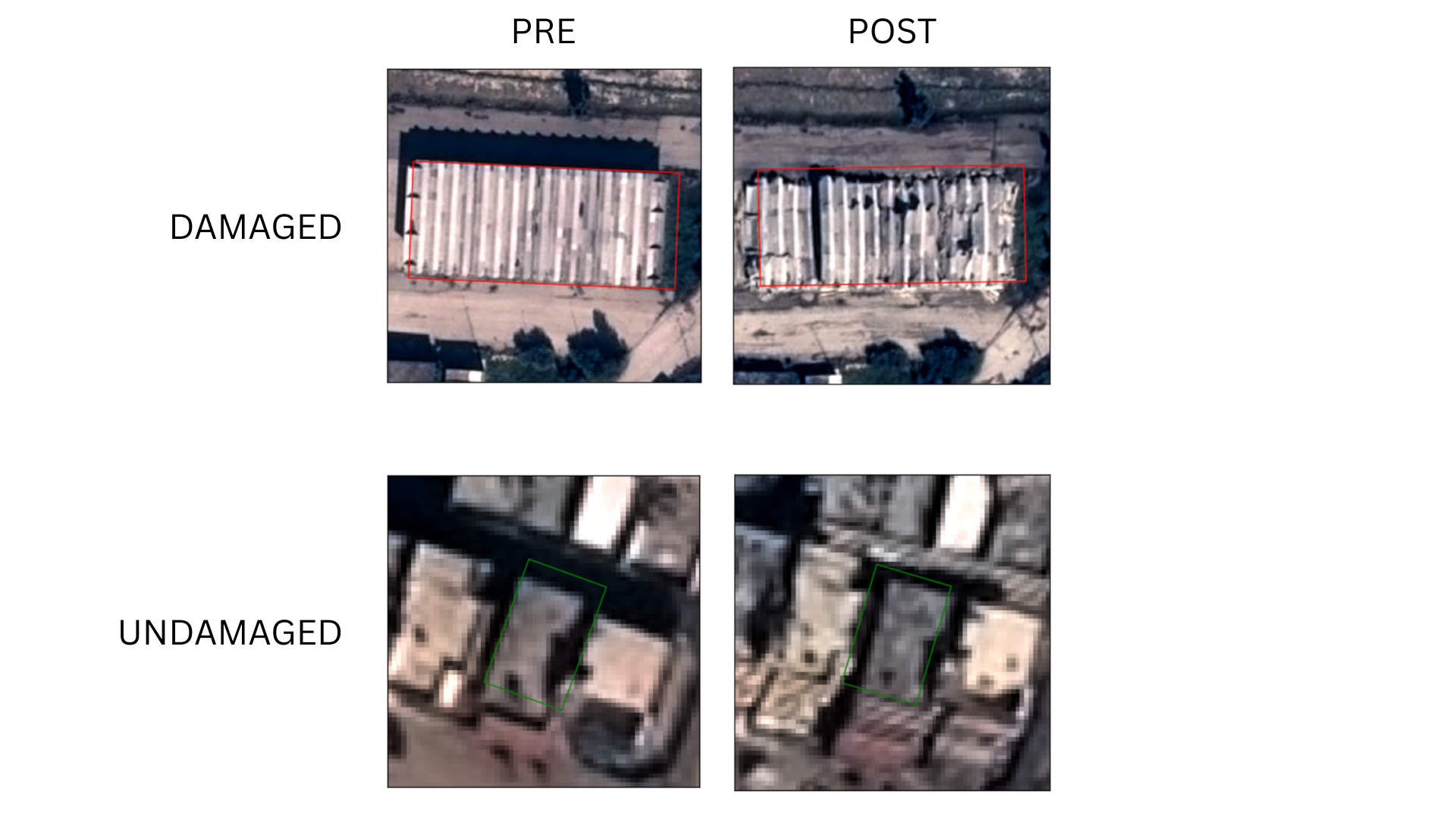

Example of building patches extracted from post-event imagery for training the first model.

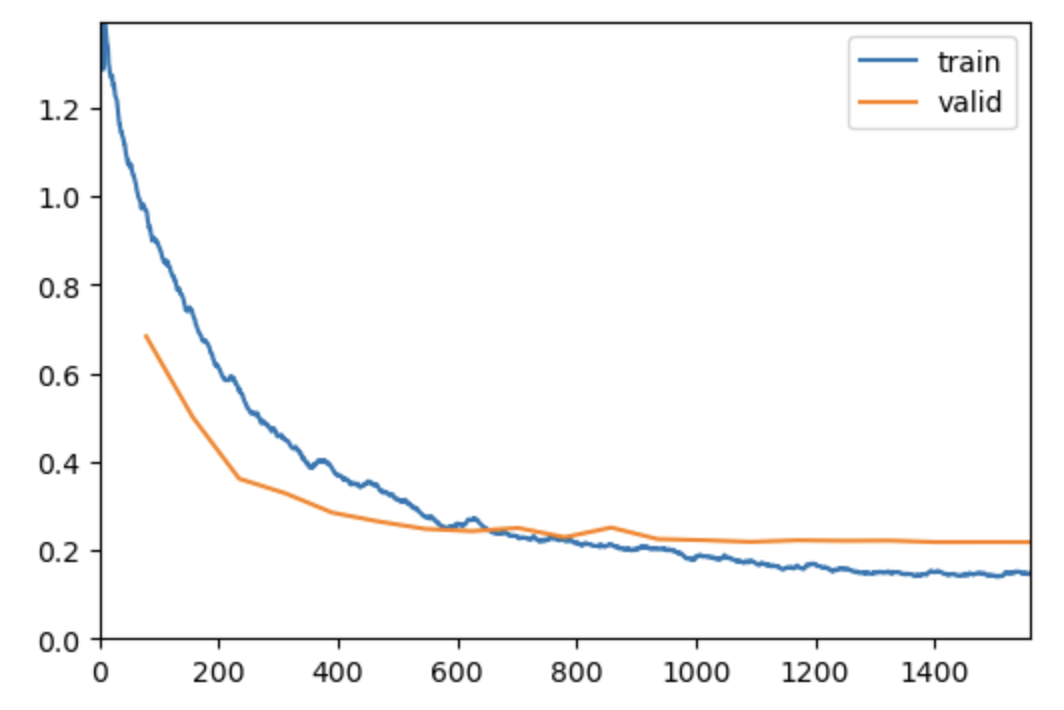

We then used fastai with a ResNet34 backbone and the fit_one_cycle training strategy. The task was framed as binary classification: 0 = undamaged, 1 = damaged.

We made a few iterations and the best results were achieved with data augmentation that wielded the following training results:

Training results of our first model using only post-event imagery (F-score Valid = 0.89 at epoch 13).

This simple setup already provided competitive scores on the leaderboard.

| SCORE | ADIYAMAN_F1 | ANTAKYA_EAST_F1 | CHINA_F1 | MARASH_F1 |

|---|

| Training Post Images Only | 0.80392 | 0.933 | 0.734 | 0.819 | 0.787 |

Second Model: Pre- and Post-Event with Siamese Network

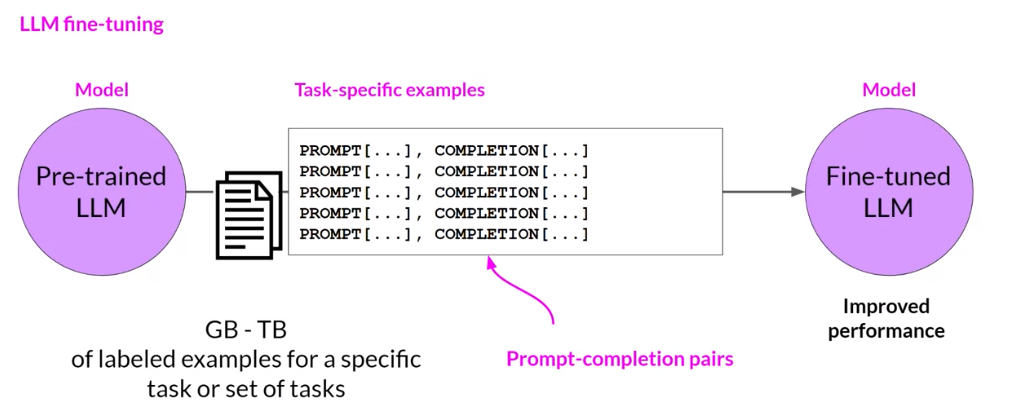

To leverage both pre- and post-event imagery, we trained a Siamese network.

A Siamese network is a type of neural network architecture that takes two inputs and learns to compare them. In our case, the inputs were pre-event and post-event building image patches.

Image Registration

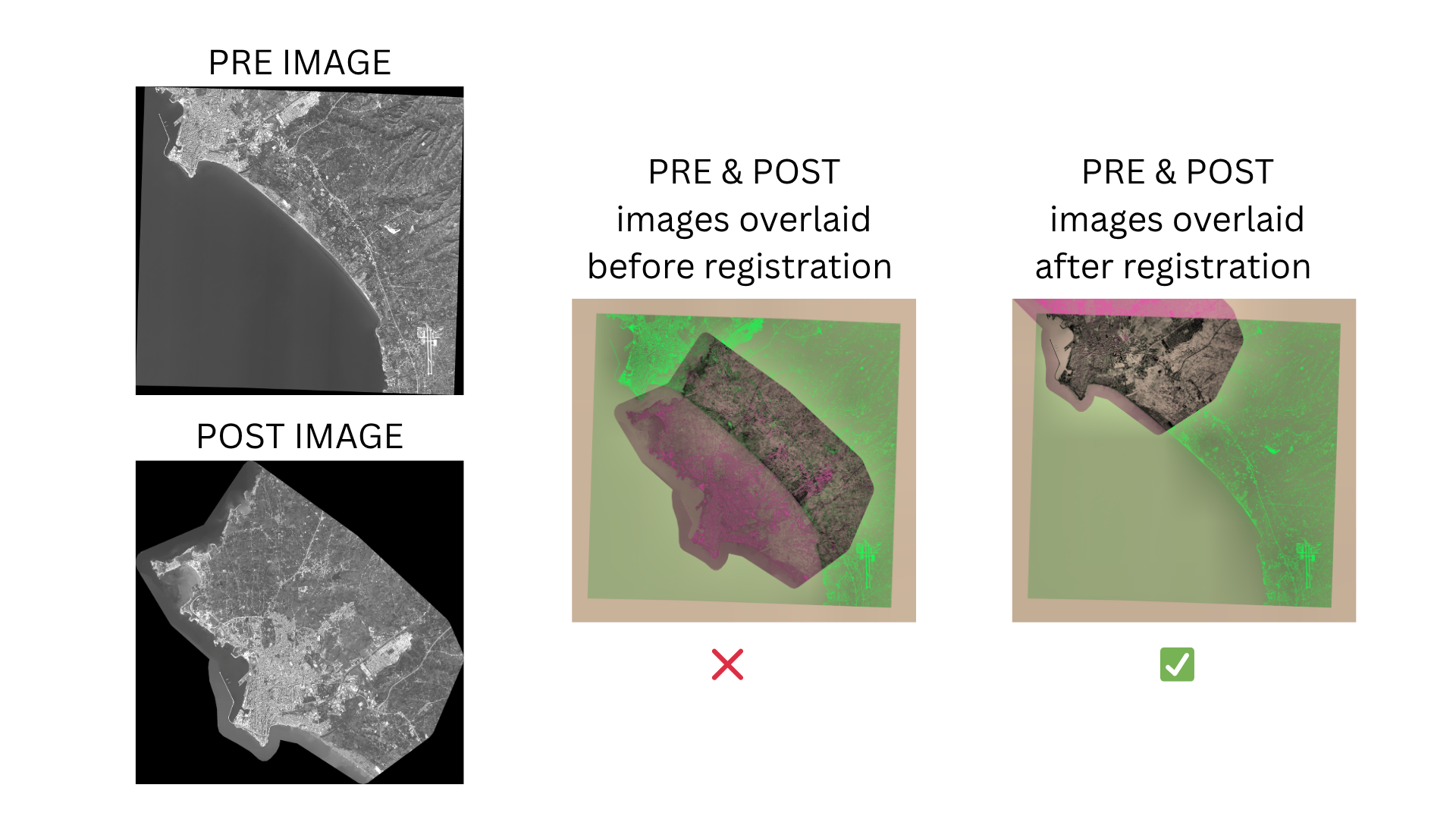

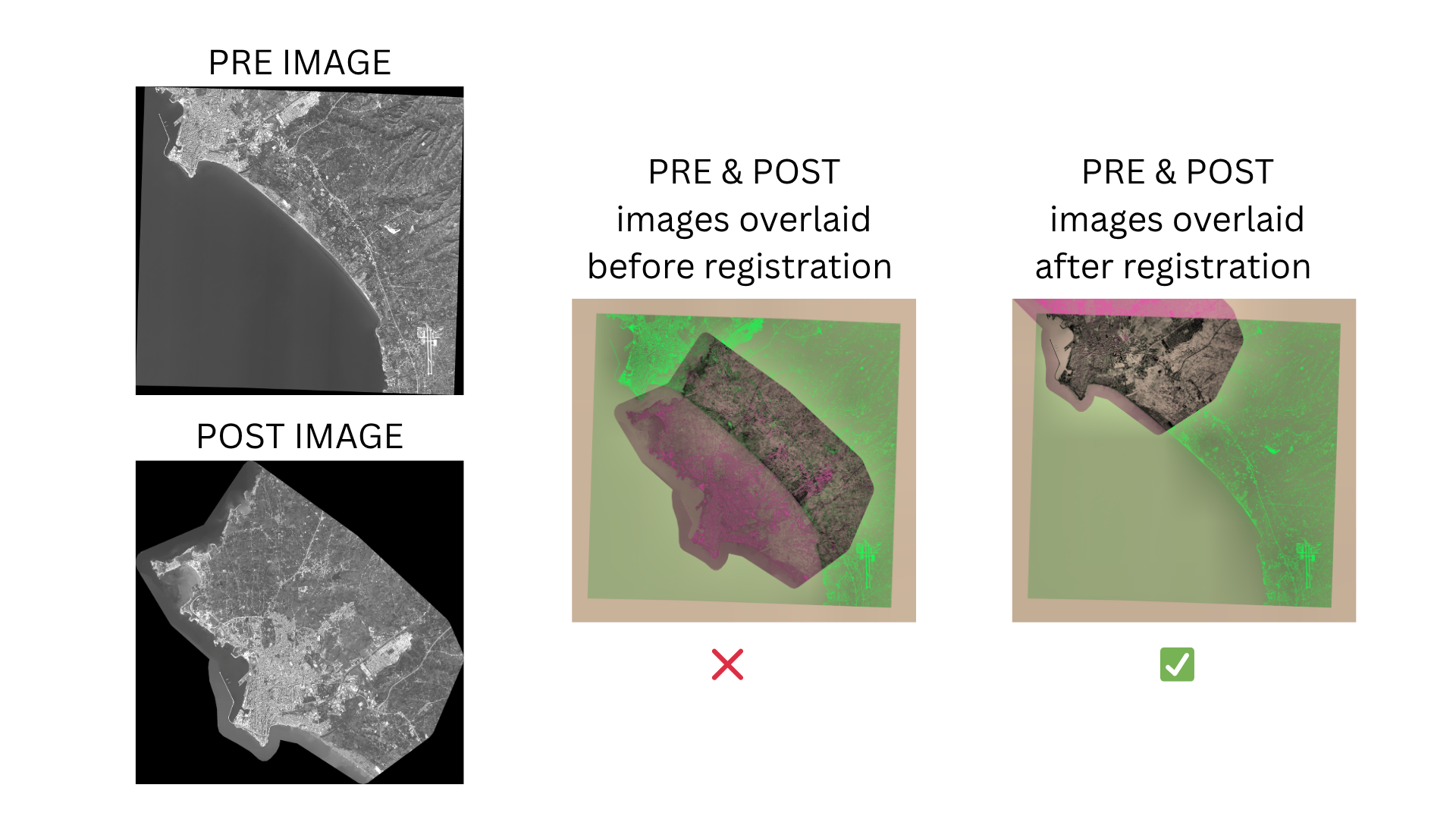

Before feeding the images into the network, we performed feature-based image registration.

As explained in the challenge overview, building annotations were only provided for the post-event imagery,

and pre-event images sometimes came from different satellites with slightly different angles,

resolutions, or positions. Feature-based registration detects and describes distinctive key points in both images,

matches them, and computes a transformation to align the pre-event image to the post-event one.

For keypoint detection and description, we relied on modern deep-learning-based local feature extractors,

specifically SuperPoint and DISK. We evaluated both methods qualitatively on the dataset and selected

whichever produced more reliable and consistent correspondences for a given image pair. The resulting matches

were then refined using RANSAC (Random Sample Consensus) to remove outliers and estimate a geometric

transformation. This transformation was applied to warp the post-event buildings polygons onto the pre-event image.

This process ensured that each building polygon matched the same location in both images,

allowing the Siamese network to accurately detect changes.

Example of registered pre- and post-event images.

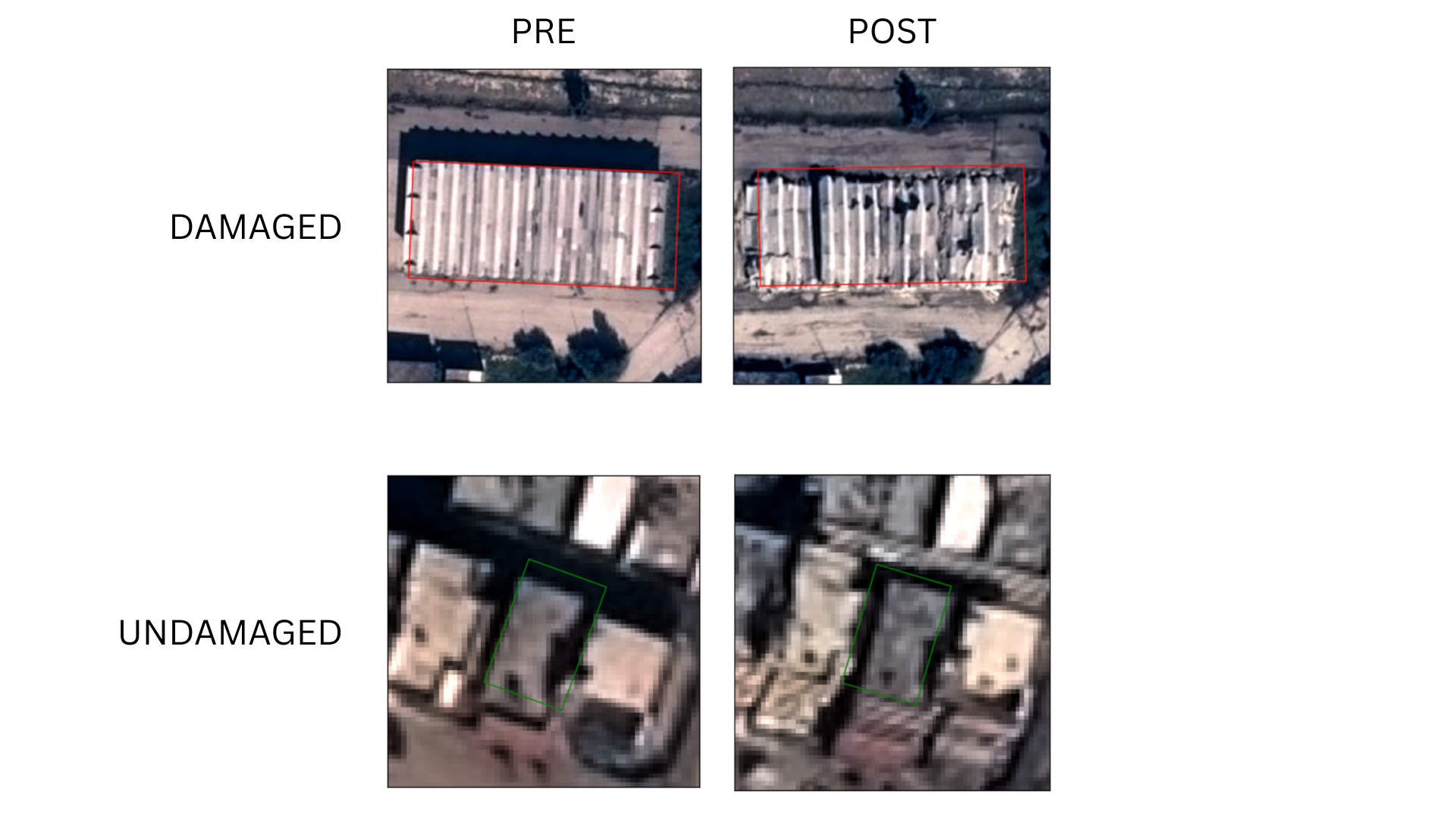

Siamese Network Training

The Siamese network consists of two identical branches (sharing the same weights) that process each

input separately to extract feature representations. These features are then compared — for example,

by computing the difference or similarity — to predict whether the building has been damaged.

This setup is particularly useful for change detection, because it focuses on differences

between the pre- and post-event imagery rather than absolute features in each image alone.

Examples of pre- and post-event image patches fed into the Siamese network for training the second model.

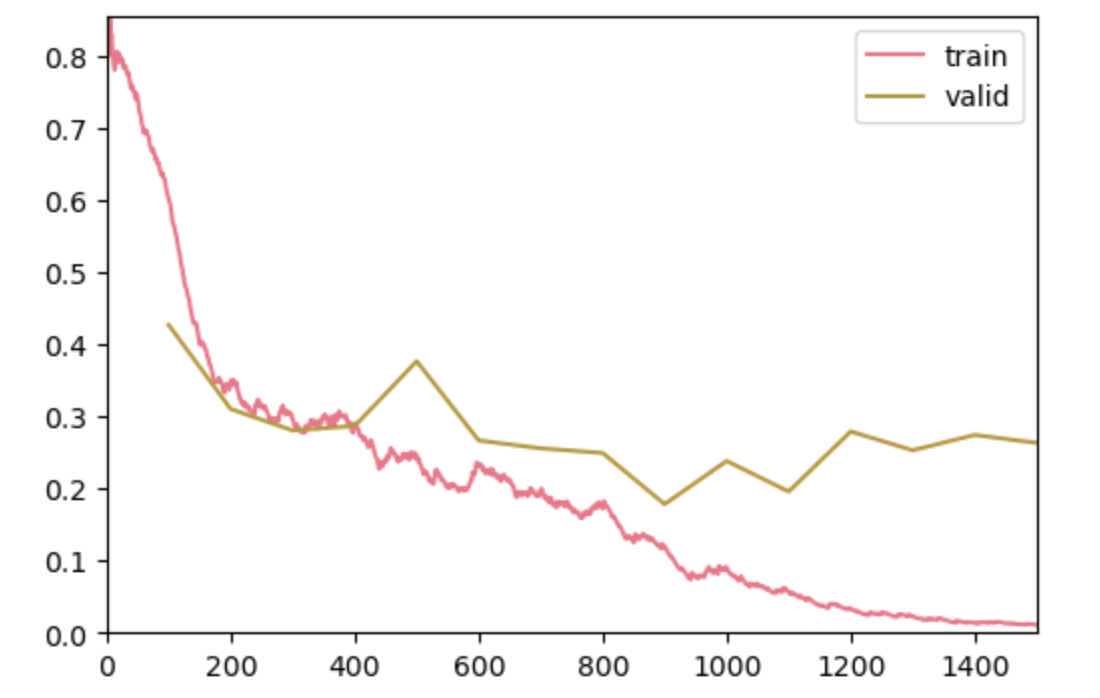

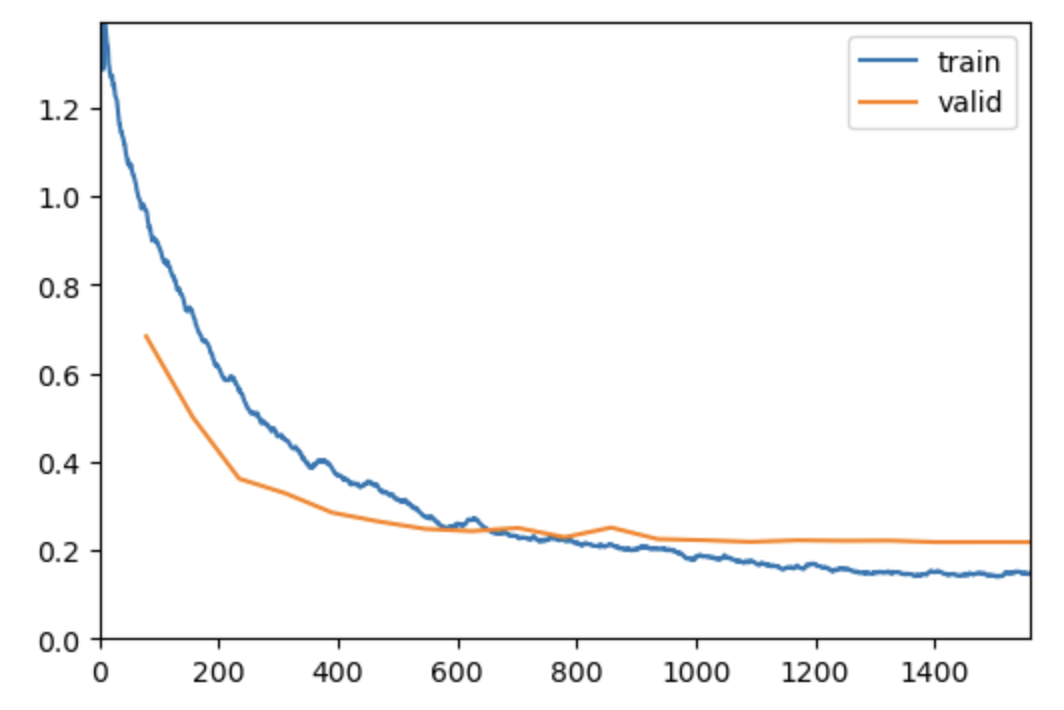

The training process was similar to our first model, using fastai and a ResNet34 backbone. This required more coding as the Siamese architecture is not natively supported in fastai.

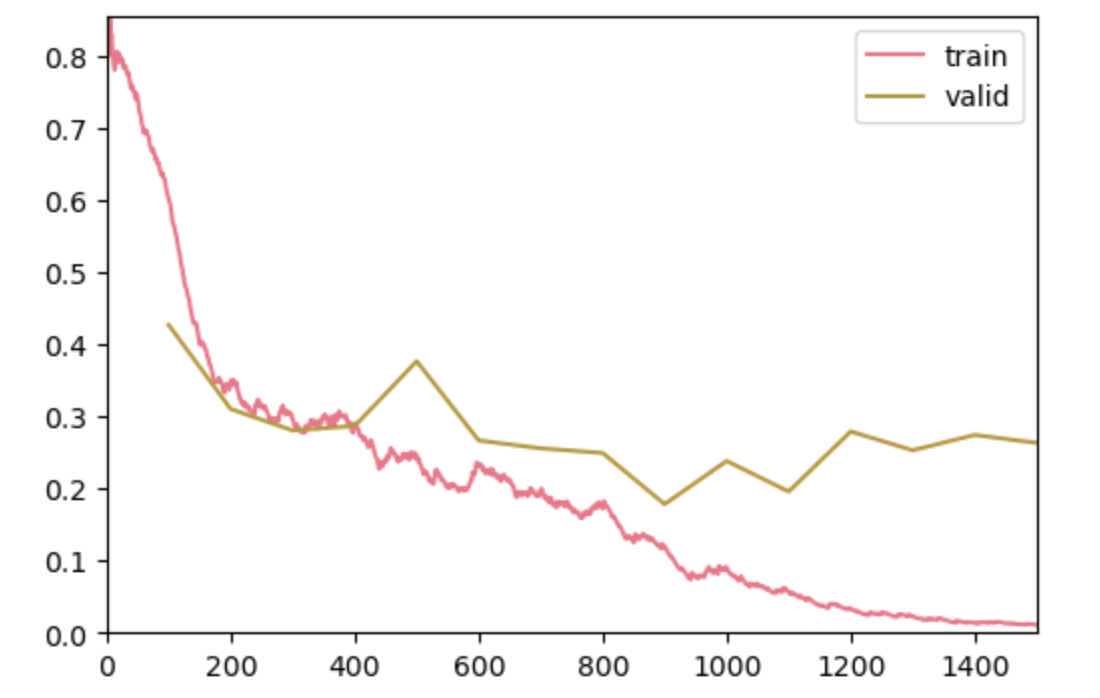

Training results of our second model using both pre- and post-event imagery with a Siamese network (F-score Valid = 0.89 at epoch 14).

This approach improved results overall, though we ran into a challenge with one of the sites.

| SCORE | ADIYAMAN_F1 | ANTAKYA_EAST_F1 | CHINA_F1 | MARASH_F1 |

|---|

| Training Post Images Only | 0.80392 | 0.933 | 0.734 | 0.819 | 0.787 |

| Training Pre- and Post-Images | 0.82116 | 0.889 | 0.750 | 0.829* | 0.848 |

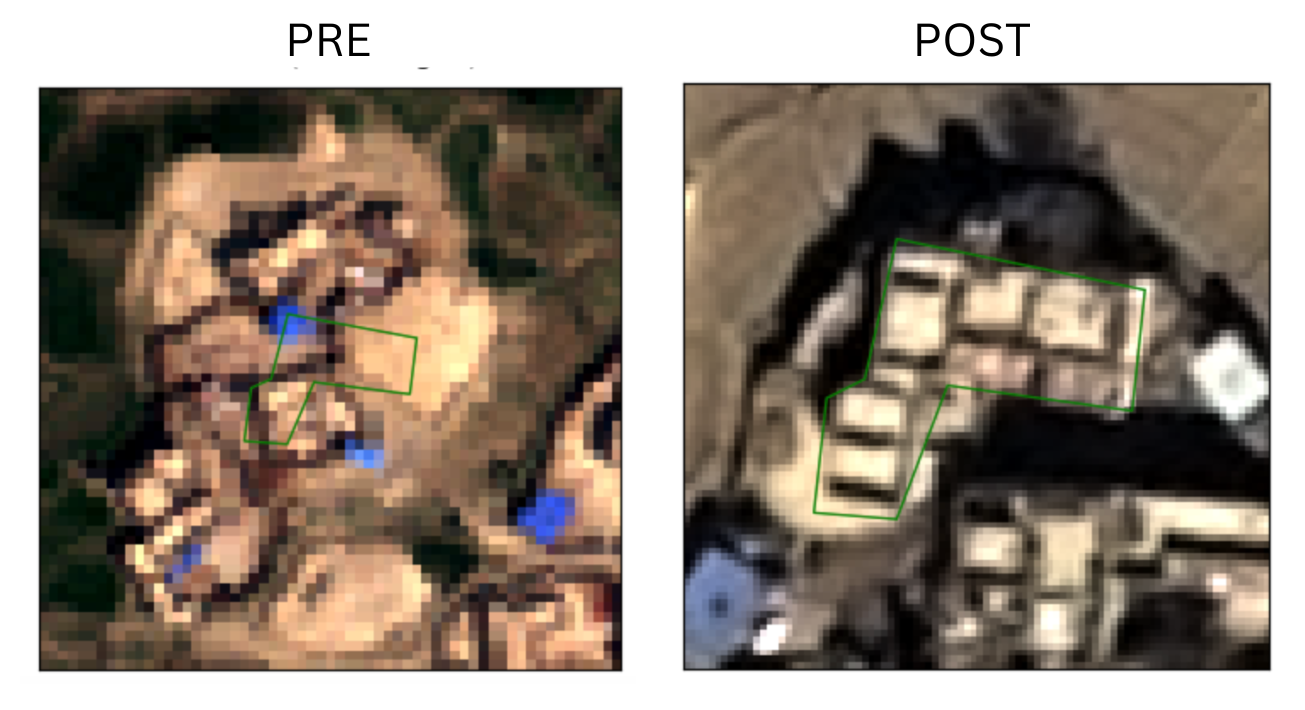

For the Cogo / China site (*) (one of the four leaderboard sites), the registration did not work well.

The pre-event imagery was of much lower resolution than the post-event imagery, making it difficult to find matching key points for alignment. As a result, the patch extraction for pre-event images was not accurate. That is why, we decided to not use Siamese predictions for this site. Instead, we used majority votes on some variants of our first model that use only post-event imagery.

Example of misaligned pre- and post-event patch for the China site.

Combining Models: Majority Vote

To increase robustness, we combined predictions:

- For each building, we gathered results from both the post-event-only model and the Siamese network.

- A simple majority vote was applied to produce the final label.

This ensemble strategy helped balance the strengths of both approaches.

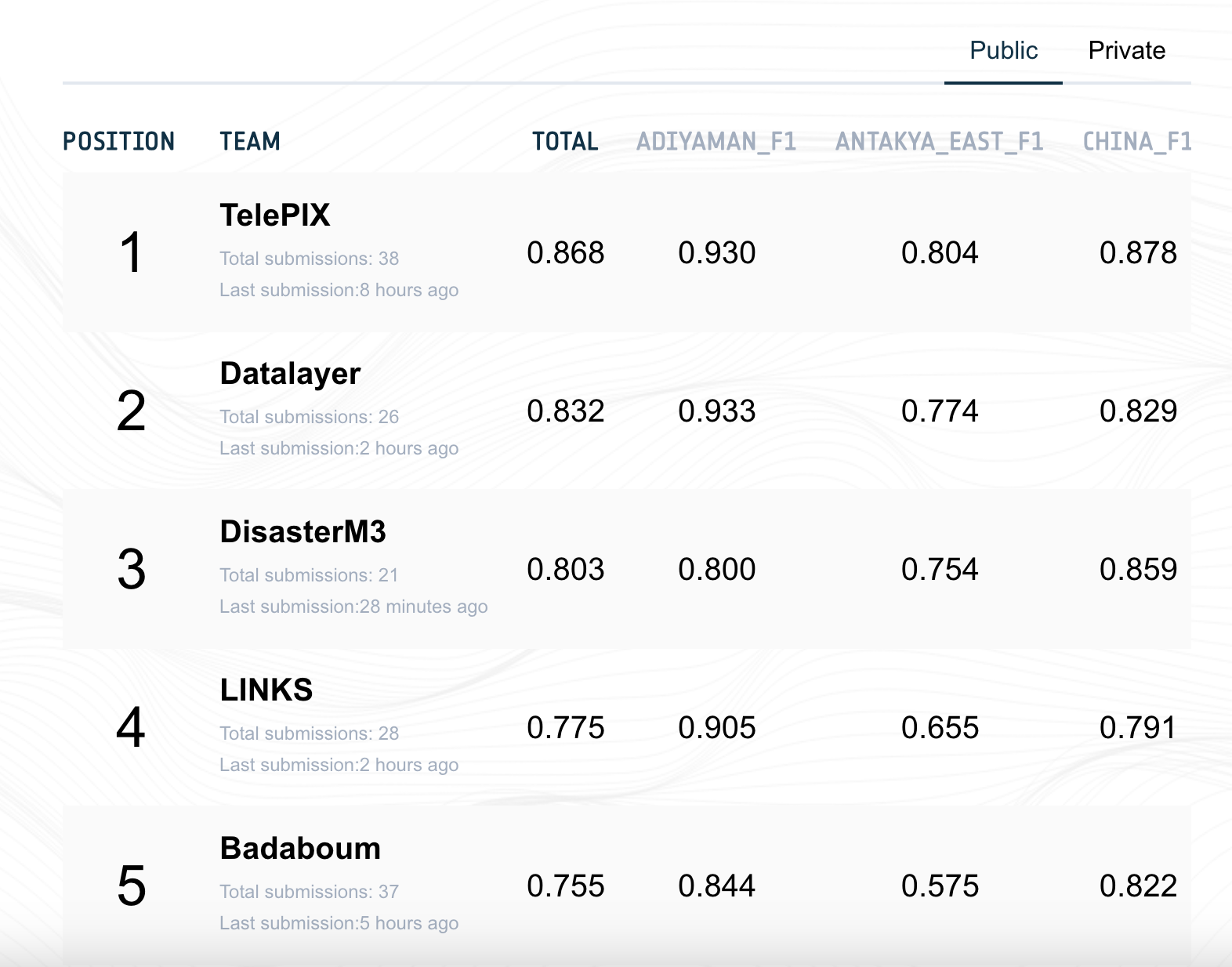

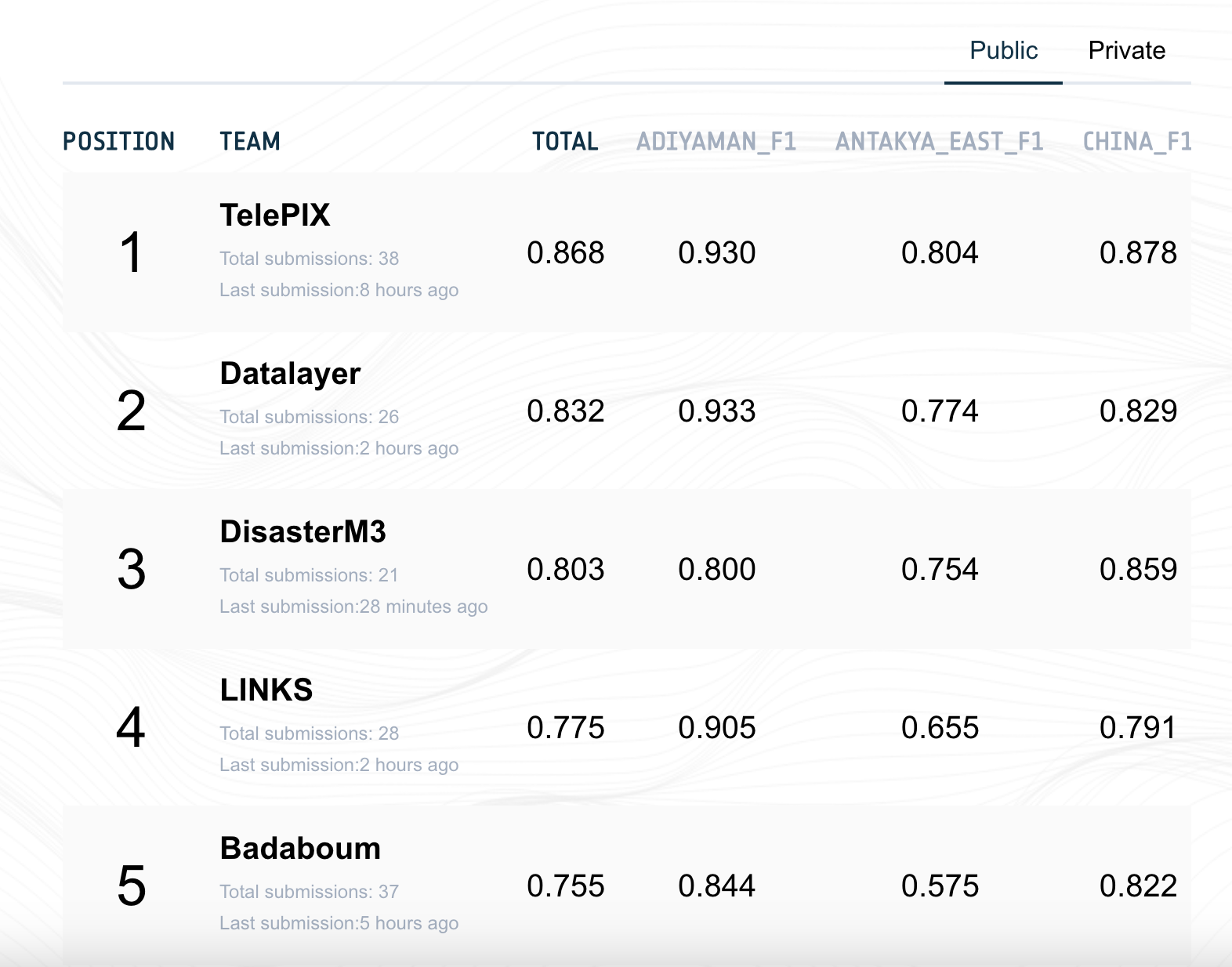

At the end of Phase 1, this approach earned us second place on the leaderboard for phase 1.

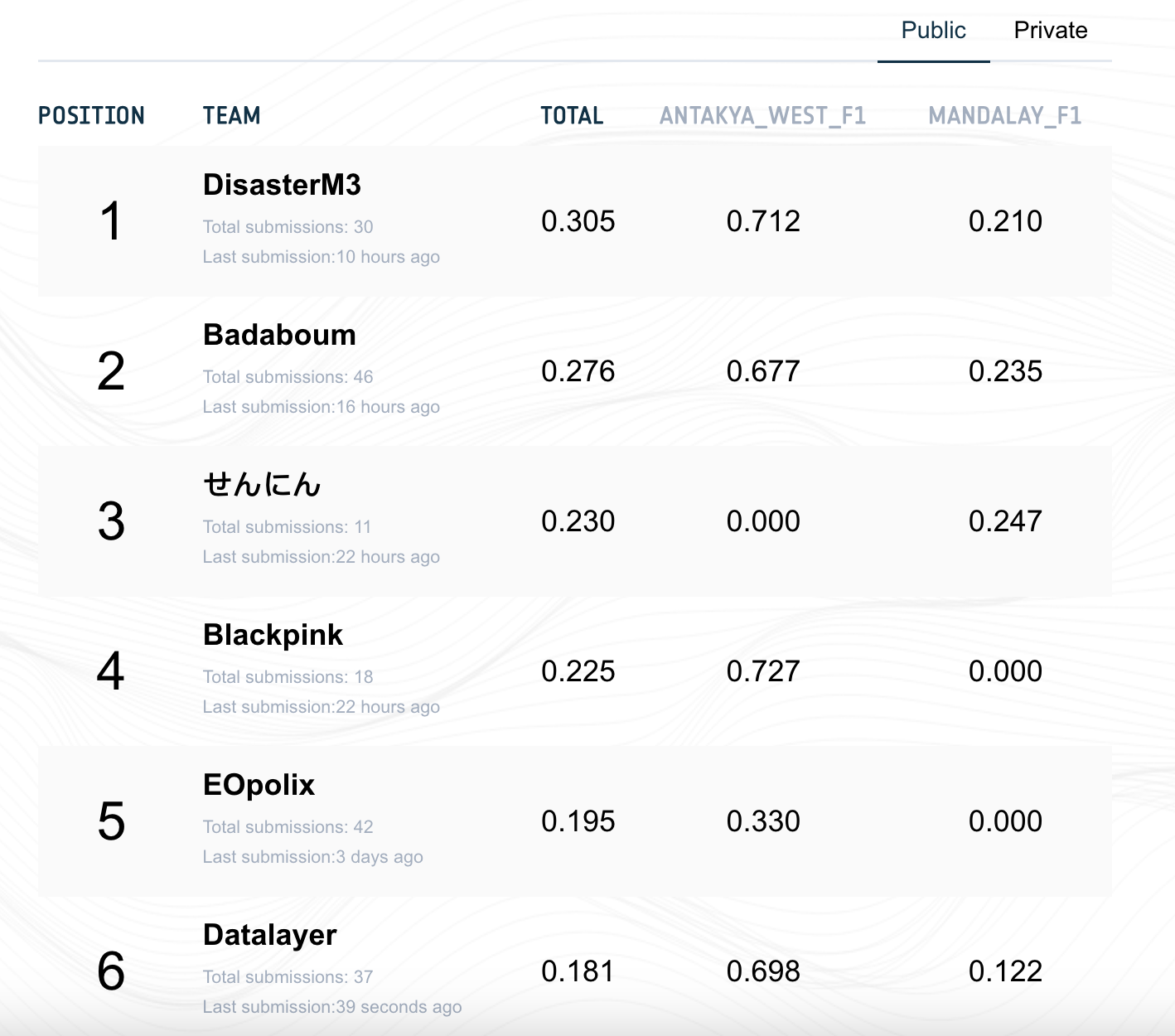

Phase 1 leaderboard showing our second place (Team: Datalayer).

Note that this was the public leaderboard score. The private leaderboard score could differ. No information about the split between public and private leaderboard sites was provided. Only the final result after Phase 2 was provided.

Phase 2: Predicting on New Sites

In the second phase, we aimed to apply our trained models to new, unseen sites. We received pre- and post-event imagery for two new earthquake sites along with their building annotations, but of course no labels were provided.

The first new site was Hatay / Antakya West and contained approximately 19,000 buildings. The second site was Mandalay with, in this case, approximately 447,000 buildings. This high number of buildings posed a computational challenge, as we had to process a large volume of image patches efficiently.

For the predictions, we used the same models as in Phase 1 without any retraining. We applied the same patch extraction, image registration (for the Siamese model), and majority voting strategy for the Hatay / Antakya West site.

For the Mandalay site, the same patch misalignment issue as in the Phase 1 China site occurred, so we decided to rely solely on the post-event-only model and its variants for predictions.

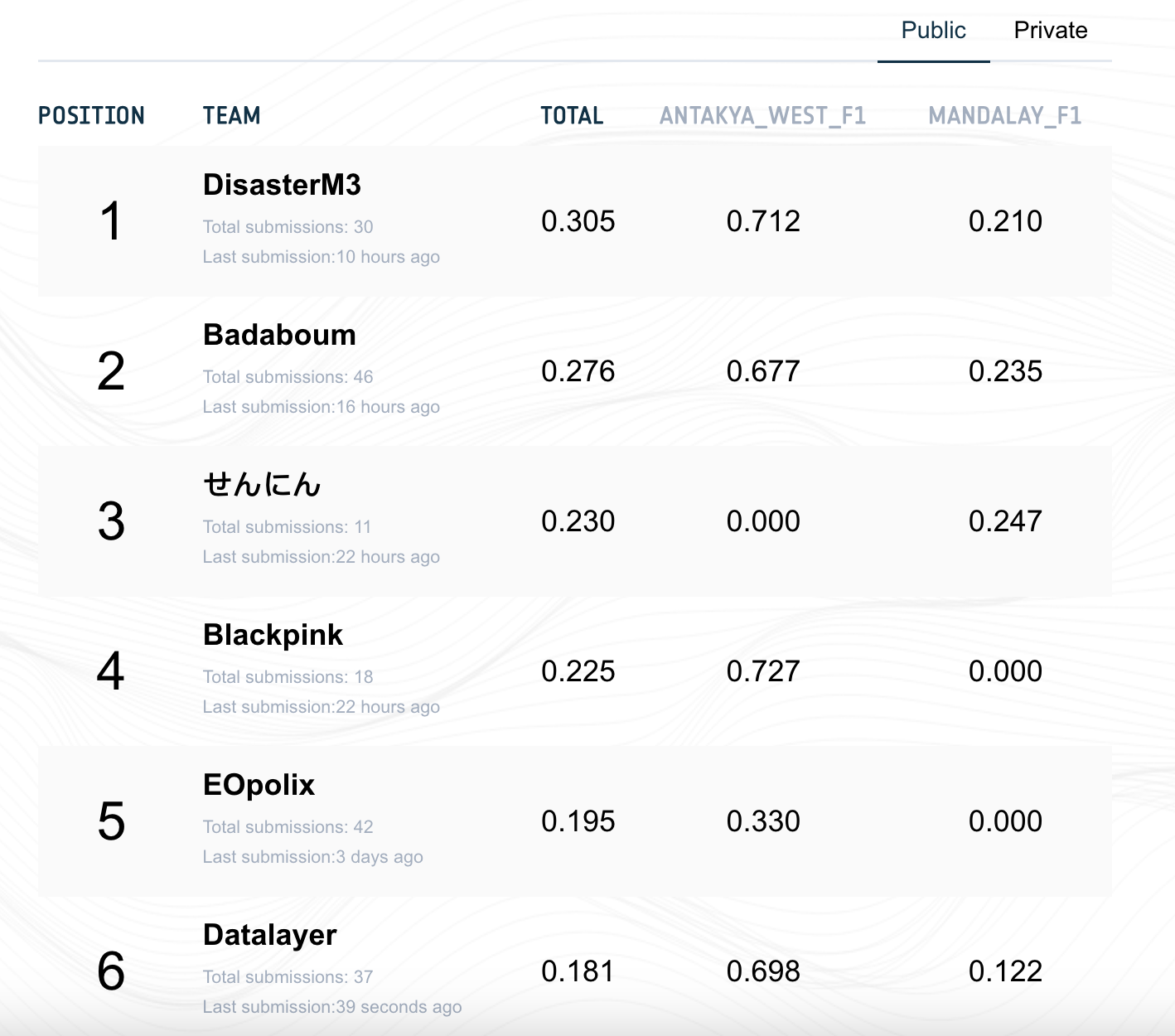

At the end of Phase 2, our approach earned us 6th place on the leaderboard for phase 2.

Phase 2 leaderboard showing our 6th place (Team: Datalayer).

Note that this was the public leaderboard score. The private leaderboard score could differ. No information about the split between public and private leaderboard sites was provided. Only the final result after Phase 2 was provided.

The score on the Mandalay site was particularly low and this is true for all teams. A possible reason is the split between the public and private leaderboard where the public leaderboard was based on a very small subset of the Mandalay site that was not easy to predict. This is just a hypothesis as no information was provided by the organizers about this. But the public phase 2 leaderboard score was obviously not representative of the overall performance on the Mandalay site as we can see from the final results.

Note also that some global scores seem inconsistent with the site-level scores. No explanation was provided by the organizers about this.

Final Results

On September 30, 2025, the final results were announced, and we secured 2nd place overall in the challenge.

This result takes both phases into account with public and private leaderboard scores with 40% weight for phase 1 and 60% weight for phase 2.

| Rank | Team | Score |

|---|

| 1st | Telepix | 0.7066794 |

| 2nd | Datalayer | 0.6697664 |

| 3rd | DisasterM3 | 0.6597626 |

| 4th | Badaboum | 0.6469298 |

Future Improvements

While our models performed well, there are several avenues for further enhancement:

- Better pre-event image alignment – Improving registration methods, including testing intensity-based approaches in addition to feature-based ones, could boost Siamese network performance on challenging sites like Cogo/China or Mandalay.

- Pan-sharpening of imagery – Using panchromatic bands to enhance the spatial resolution of low-resolution color images could improve detection of subtle building damage.

- Exploring alternative dual-image networks – Testing other architectures designed to process two images simultaneously could outperform the Siamese setup for change detection.

- Enriching training dataset – Incorporating additional earthquake-related imagery could improve model generalization to unseen regions.

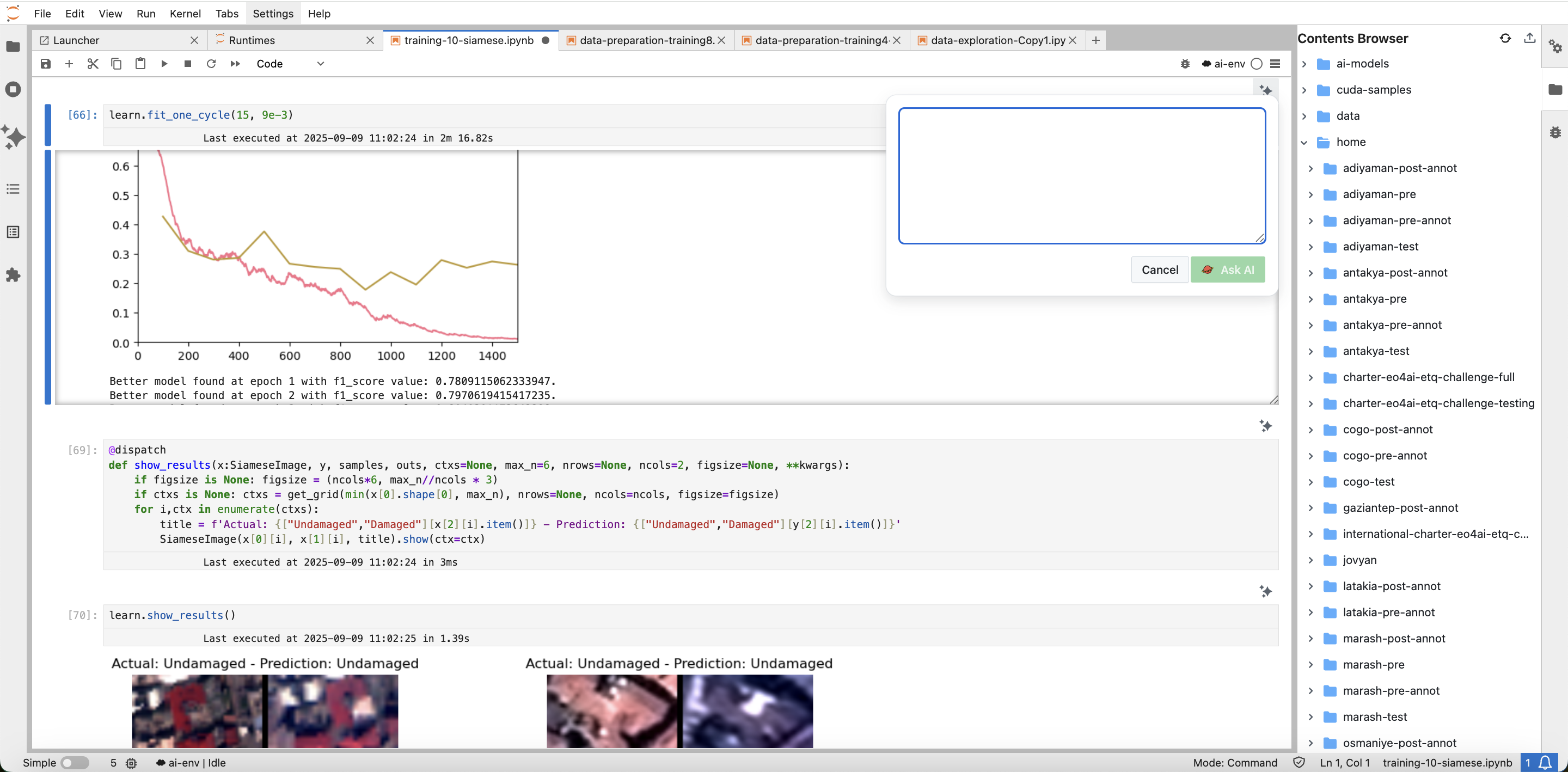

How Datalayer Solution Helped

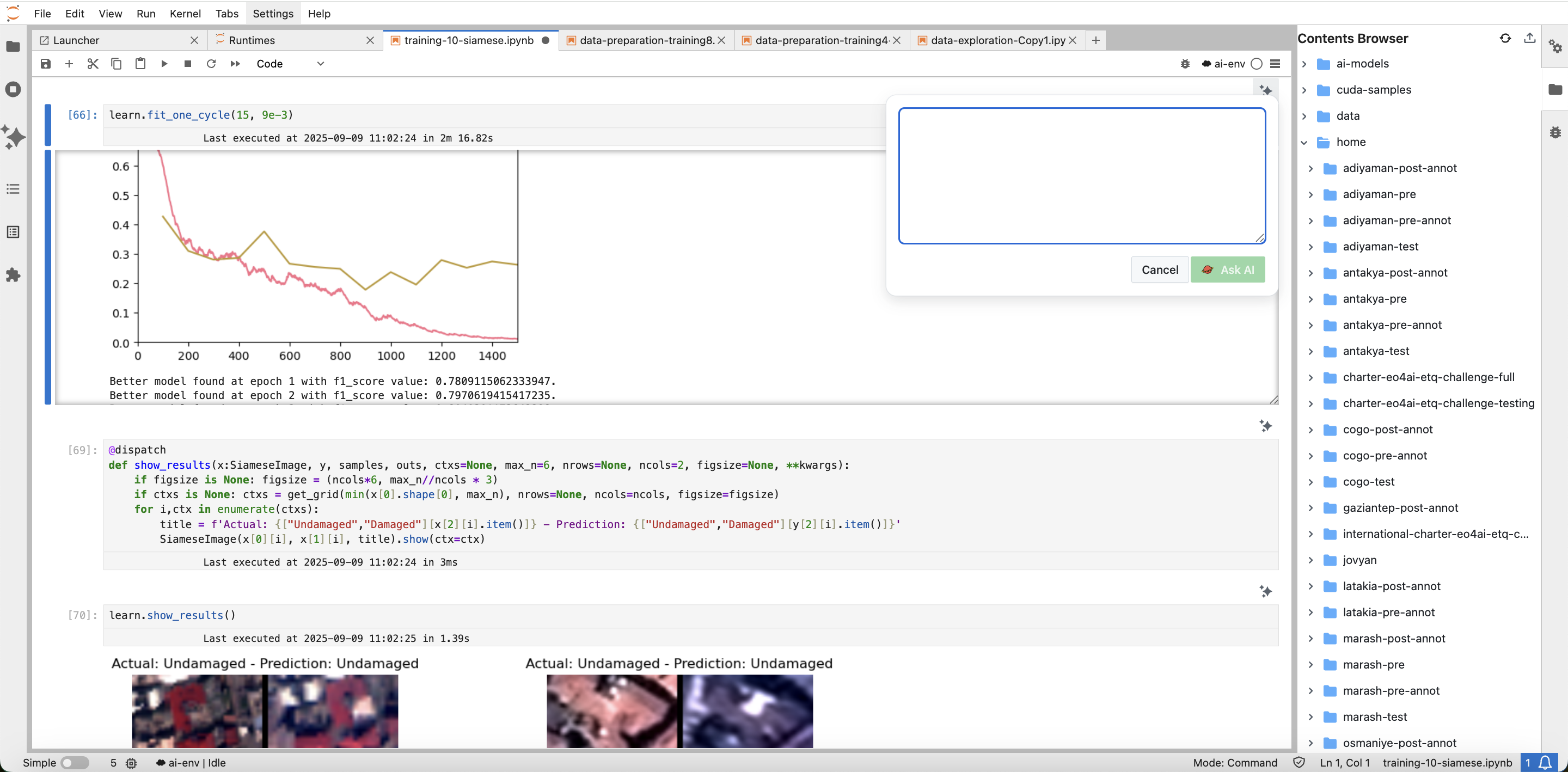

A big reason we were able to iterate quickly and experiment with different models was the Datalayer solution. With Datalayer, we could:

- Easily download the 475 GB challenge dataset thanks to the seamless integration of high-capacity cloud storage and compute runtimes.

- Access GPU runtimes (A100) directly from JupyterLab with 2 clicks, making it straightforward to train our models quickly.

- Benefit from AI assistance through available Agents, which helped streamline our workflow.

- Move data between local and remote environments for flexible experimentation.

This allowed our team to focus on modeling and experimentation rather than infrastructure and boilerplate code, which was crucial given the tight challenge timelines.

Notebook in JupyterLab using Datalayer Runtime with GPU access, integrated cloud data storage and AI assistance.

Main Challenges Faced & Lessons Learned

Along the way, we faced the following main challenges:

-

Misalignment for some sites – As already mentioned, registration was a major obstacle, particularly for low-resolution or multi-sensor pre-event images (e.g., Cogo/China and Mandalay). The lack of perfect alignment significantly reduced the effectiveness of Siamese networks.

-

Misalignment even in post-event imagery – For certain sites, even the post-event images were not perfectly aligned with the building polygons. This was not something we could easily fix on our end, and in many cases it appeared to be a data quality issue. This introduced noise in both training and evaluation.

Example of misaligned post-event patches where building polygons do not match the imagery.

Despite these issues, the competition demonstrated that relatively simple deep learning approaches, when combined with careful data preprocessing, can already provide valuable tools for rapid post-disaster mapping.

A key takeaway from this challenge is that rapid iteration and robust infrastructure are essential. With tight competition deadlines, efficient data access, scalable compute resources, and streamlined experimentation tools were critical for testing multiple approaches and refining our models effectively.

From this experience, we also realized that, as many already know, notebooks are excellent for exploration and experimentation, but they can quickly become messy and hard to reuse. Python scripts, on the other hand, are better suited for reusable, modular code.

This insight is something we aim to incorporate into the Datalayer solution: enabling seamless work with both notebooks and Python scripts remotely, with easy handling of imports and project organization. If time permits, we would also love to clean up our code and make it publicly available, so others can benefit from our approach.

Another insight was that remote-local data transfer is an extremely valuable feature, allowing seamless experimentation between local and cloud environments. However, we noticed it could be improved further to handle larger datasets more efficiently.

We loved taking part in the challenge and are excited to present our solution in Strasbourg on October 6 to the Charter Board.

Testing our Datalayer solution against real use cases like this is incredibly valuable.

This helps us identify areas for improvement and better understand the needs of data scientists working with geospatial data.